Lately, I have been trying to improve transport security (read: SSL settings and ciphers) for the online banking sites of the banks I am using. And, before you ask, yes, I enjoy fighting windmills.

Quick refresher on SSL / TLS before we continue: There are three things you can vary when choosing cipher suites:

- Key Exchange: When connecting via SSL, you have to agree on cryptographic keys to use for encrypting the data. This happens in the key exchange. Example: RSA, DHE, …

- Encryption Cipher: The actual encryption happens using this cipher. Example: RC4, AES, …

- Message Authentication: The authenticity of encrypted messages is ensured using the algorithm selected here. Example: SHA1, MD5, …

After the NSA revelations, I started checking the transport security of the websites I was using (the SSL test from SSLLabs / Qualys is a great help for that). I noticed that my bank, which I will keep anonymous to protect the guilty, was using RC4 to provide transport encryption. RC4 is considered somewhere in between “weak” and “completely broken”, with people like Jacob Applebaum claiming that the NSA is decrypting RC4 in real time.

Given that, RC4 seemed like a bad choice for a cipher. I wrote a message to the support team of my bank, and received a reply that they were working on replacing RC4 with something more sensible, which they did a few months later. But, for some reason, they still did not offer sensible key exchange algorithms, insisting on RSA.

There is nothing inherently wrong with RSA. It is very widely used and I know of no practical attacks on the implementation used by OpenSSL. But there is one problem when using RSA for key exchanges in SSL/TLS: The messages are not forward secret.

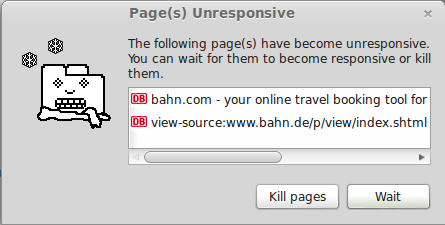

What is forward secrecy? Well, let’s say you do some online banking, and some jerk intercepts your traffic. He can’t read any of it (it’s encrypted), but he stores it for later, regardless. Then something like Heartbleed comes along, and the same jerk extracts the private SSL key from your bank.

If you were using RSA (or, generally, any algorithm without forward secrecy) for the key exchange he will now be able to retroactively decrypt all the traffic he has previously stored, seeing everything you did, including your passwords.

However, there is a way to get around that: By using key exchange algorithms like Diffie-Hellman, which create temporary encryption keys that are discarded after the connection is closed. These keys never go “over the wire”, meaning that the attacker cannot know them (if he has not compromised the server or your computer, in which case no amount of crypto will help you). This means that even if the attacker compromises the private key of the server, he will not be able to retroactively decrypt all your stuff.

So, why doesn’t everyone use this? Good question. Diffie-Hellman leads to a slightly higher load on the server and makes the connection process slightly slower, so very active sites may choose to use RSA to reduce the load on their servers. But I assume that in nine of ten cases, people use RSA because they either don’t know any better or just don’t care. There may also be the problem that some obscure guideline requires them to use only specific algorithms. And as guidelines update only rarely and generally don’t much care if their algorithms are weak, companies may be left with the uncomfortable choice between compliance to guidelines and providing strong security, with non-compliance sometimes carrying hefty fines.

So, my bank actually referred to the guidelines of a german institution, the “deutsche Kreditwirtschaft”, which is an organisation comprised of a bunch of large german banking institutes. They worked on the standards for online banking in germany, among other things.

So, what do these security guidelines have to say about transport security? Good question. I did some research and came up blank, so I contacted the press relations department and asked them. It took them a month to get back to me, but I finally received an answer. The security guidelines consist of exactly one thing: “Use at least SSLv3“. For non-crypto people, that’s basically like saying “please don’t send your letters in glass envelopes, but we don’t care if you close them with glue, a seal, or a piece of string.”

Worse, in response to my question if they are planning to incorporate algorithms with forward secrecy into their guidelines, they stated that the key management is the responsibility of the banks. This either means that they have no idea what forward secrecy is (the reponse was worded a bit hand-wavy), or that they actually do know what it is, but have no intention of even recommending it to their member banks.

This leaves us with the uncomfortable situation where the banks point to the guidelines when asked about their lacklustre cipher suites, and those who make the guidelines point back at the banks, saying “Not my department!“. In programming, you call that “circular dependencies”.

So, how can this stalemate be broken? Well, I will write another message to my bank, telling them that while the guidelines do not include a recommendation of forward secrecy, they also do not forbid using it, so why would you use a key made of rubber band and rocks if you could just use a proper, steel key?

And, of course, the more people do this, the more likely it is that the banks will actually listen to one of us…